Schwalbe, Young on Bumblebee Gobies research, findings

Gemma Mueller ‘27

muellergal@lakeforest.edu

JOUR 320 Writer

In Lillard Science Center, black and yellow fish swim in several bubbling tanks of water. These fish have been providing a group of students with biological knowledge unknown to humans, until now.

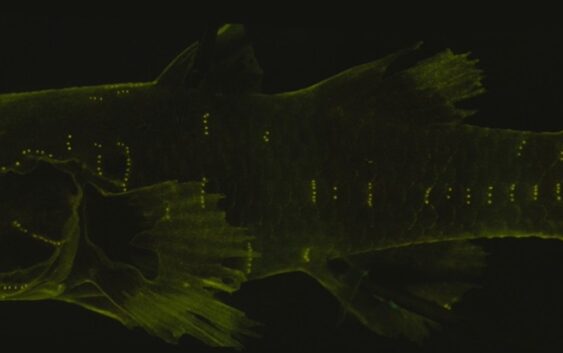

Fish have a sensory system called a lateral line, which helps them to detect their surroundings and hunt for prey. The lateral line is like a set of pores that run alongside the outside of the fish’s body.

The singular pores are called neuromasts, which are like a human’s hair follicle. When the water moves, the hairs feel it, just like how we feel a breeze.

But the Bumblebee Gobies in Dr. Margot Schwalbe’s lab, like other fish in the goby family, have a special lateral line pattern. The neuromasts that make up their lateral line are functionally superficial. This means that the pores are on the outside of the skin, instead of underneath it.

But why and how does this work? This is what senior Zoey Young, 22, and her colleagues are trying to figure out.

They are trying to understand the connection between the function and structure of the goby’s lateral line, and how it helps the fish detect their prey. This lateral line structure is currently “understudied” when it comes to prey detection, according to Young.

“We are trying to see whether they use their lateral line to detect their prey, or will they only rely on their visual systems and other things like that,” Young said.

The students test the fish on their ability to sense brine shrimp both in the dark and light, and with and without their lateral line. To test the fish without the use of their lateral line, the students temporarily disable their senses with anesthesia. This way, their use of the lateral line return.

When the lights are on, the gobies can see their prey, but if the light is off, the fish must rely on their other senses. When the lateral line is temporarily gone, they struggle with detecting their prey.

“We wonder whether they will even be able to catch their prey. And they do! It just takes them longer,” Young said.

They perform these tests in a corner of the lab shaded by black out curtains. The students spend about 10 hours a week in the lab, but now they spend even longer, she says. The students are struggling to get the gobies to eat.

Although the gobies are cold-blooded, which means they can go several days without a meal, they do need to eat periodically to survive. Dead fish have no real use in data collection.

“Live animals just never do what you want them to do,” Young said.

The lab has tested several groups of fish over the past two semesters.

“I keep buying more fish and they just sit there and watch their prey swim,” Schwalbe said., “You know they can do it, but they won’t do it under the camera.”

The lab students have been trying new tactics, like isolating a single goby in a separate bucket with one shrimp. Often the gobies just watch the prey swim around, but sometimes the students get lucky, and the fish will eat.

Even though the gobies can be stubborn creatures, Young remains persistent. This kind of research, relating to the lateral line pattern of bumblebee gobies, is brand new to the field of biology.

On March 21, Schwalbe’s students presented their research at a neuroscience conference in downtown Chicago for the first time, which is unusual.

Such conferences are often focused on the human application of animal research.

Work related to animals, and only to animals, is often overlooked in scientific spaces, Young said.

“A lot of people ask me what the bigger purpose of our research is,” she says. “As humans, we struggle to comprehend that we are doing this research for the sake of knowledge.”

However there may, in fact, one day be human applications, according to Schwalbe.

“To apply my research in a greater sense, the more we learn about lateral line function, the more it could apply to underwater vehicles,” she said.

“There are engineering groups that make sensors like neuromasts to put onto underwater vehicles, it’s called bio inspired engineering.”

Young and other students involved with the Schwalbe Lab also presented their work at the Lake Forest College Student Symposium on April 8. The bumblebee gobies had their very own poster

“I am consistently amazed by the quality of research being produced from this school, makes me proud to be a biology student at Lake Forest College,” Young said.

As the year comes to a close, the research will continue; The findings to be published as soon as possible according to Schwalbe.

For now, Young is preparing to graduate, and looks back on her time spent with her colleagues, and the gobies, in the lab.

“It’s really inspiring to know that there is a group of people who are so dedicated to learning more about the world and, in doing so, helping educate others,” Young added.